Scrum of Scrums – A Communication Thermometer

January 20, 2014

I’ve noticed that a lot of organizations seem to have problems with Scrum of Scrums. Some coaches refrain from recommending them altogether while others might use them with low expectations. Without making too many generalizations I’d like to describe one of my more positive experiences using Scrum of Scrums – as an indicator of our ability to work together.

My assignment was to coach a Scrum project with ~100 members and seven development teams distributed over three countries. One of the pains that were brought to my attention early on was how dysfunctional the Scrum of Scrums was. All the ScrumMasters and the project manager would have a teleconference three times a week where the ScrumMasters would take turns giving status reports(!) and complaining about the problems they had. I was approached by some of the ScrumMasters asking me if we shouldn’t have the meeting less frequently since “nothing new is being said. The same problems are being brought up in every meeting.”. I asked them if they thought the real problem was the frequency of the meetings or their inability to solve problems between the meetings. They kind of recognized my point and agreed to continue with the three weekly meetings for a while longer.

We began to move away from giving status reports and I also suggested that they started to write down the issues that were being brought up and make sure that unless someone claimed responsibility for actually working on an issue, they wouldn’t be allowed to keep complaining about it in this forum. My idea of writing down the issue was to create an excel-sheet or something similar in a shared folder but apparently in this organization, there would have to be a JIRA project to store such information. It also turned out that it would take about a month to create said JIRA project.

Since I had a hard time seeing that JIRA would be the way this problem got resolved, I also started working on other things in parallel. The first thing we did was to get all the ScrumMasters together to get to know each other. I managed to get the funding to fly all ScrumMasters to one of our sites and hold a retrospective and some other workshops. It was a great day with people getting to know each other but it still wouldn’t be enough. When, towards the end of that day, I asked if everyone in the room had everyone else on speed dial, the frightening answer was that no-one had anyone else’s phone number in their cells. Getting this problem solved was easy, the problem was to get everyone to use the phone numbers.

After this day together, I began requesting from each ScrumMaster to call all the others’ on a daily basis. Whether they had an issue to talk about or not, they should at least make a social call to see how the others’ were doing. This didn’t happen immediately; most thought that they’d get away without making the calls but I kept asking them about it in our one-on-one’s.

I can’t tell exactly when the transformation happened, but before the new JIRA project had been set up, I noticed that fewer and fewer issues were being brought up during the Scrum of Scrums. Instead people were having social discussions and talking about problems in a past tense. When I started inquiring about this I learned that there were still a great deal of issues but now they were being solved outside of the Scrum of Scrums. The teams (or at least their ScrumMasters) had begun caring about each other. One team even offered to send some of their developers to another country to help one of the teams there before the other team had worked up the courage to ask for external help.

In a little more than a month we went from having a meeting that didn’t help us coordinate any issues or solve any problems at all, to holding a meeting where there were no issues to coordinate and no problems to solve. This made me realize that the daily stand-up and the Scrum of Scrums might not really be any solutions in themselves, but rather indicators of how well we communicate within our teams – outside of the meetings.

High-fiving the office

February 21, 2013

This morning it took me fifteen minutes to walk past my team and get to my desk…

But that was this morning, let’s back up one month. Middle of January my team had a team building activity. Now, I know that teams aren’t built during an activity but there were reasons behind us having this activity. Anyway, as a final exercise we all got to close our eyes, relax and try to visualize what it would be like if everything in the workplace was going as we wanted. We then got to draw our internal images and present them to each other.

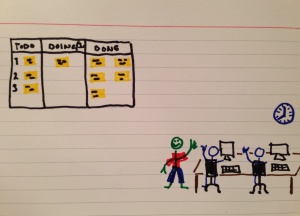

My drawing had two parts to it. One part showing a kanban board where work was flowing smoothly, representing how we worked well together as a team. The second part pictured me high-fiving my co-workers on my way to my desk, representing us having a great time together.

What I saw before me was how it would take me fifteen minutes every morning to move from the entrance to my desk because I high-fived everyone along the way, stopping to ask how they were doing and generally enjoy being with awesome people.

Some background might be in place here. My desk is at the opposite end of the building from the entrance, which means that I have to walk by the entire team every morning as I walk to my place. The thing is, that I’m an MBTI introvert. I enjoy people and company like most other people but it’s exhausting for me. Having a good time with other people makes me physically and mentally tired. Because of this I’ve been taking a detour every morning in order to get to my desk without having to pass anyone I know, that way I could save my energy for “more important stuff”.

As I looked at my drawings I realized that the first part was what we’re struggling with together as a team, but that the only thing standing between me and my vision in the second drawing was myself.

The day after the exercise I stopped for a minute after entering our floor. I took three deep breaths and began the walk to my desk. Only a few team members were at their desks so I walked up to the one colleague who I knew would understand the idea. I raised my hand and immediately got a slap. It felt good and we discussed the exercise for a while. The day after I repeated the ceremony but stopped by two of my colleagues on my way to my desk.

Since then I’ve been adding people to my daily routine and this morning I walked around high-fiving everyone at their desks, stopping to chat for a while; both personal stuff as well as job-related. I timed the walk and it took me fifteen minutes to get to my desk.

What I’ve noticed is that most people’s faces light up as I walk by for the daily slap. The guy next to me was a bit upset though, he didn’t want to always be the last one to get a high five.

I believe in the idea that we are our feelings. If I act happy, then I will be happy and I will feel happy. If I start the day with a smile and a high five, I will get a better day. Fake it till you make it so to speak. The bonus is that people around have to start their mornings with a smile and a high five as well.

So as an introvert, does this procedure consume energy? You bet it does, I have to brace myself every morning before I walk into the room.

Is it worth it? You bet it is!

Disclaimer: Not everyone enjoys a high five in the morning, especially if they’re in the middle of something and that’s okay too.

Brainstorming With Colonel Mustard

February 13, 2013

I was recently asked by a colleague to help with the format for a brainstorming exercise. The purpose of the exercise was to find new ways to reach an audience for the content our organization was developing. Both of us wanted to try something new and we really wanted the participants to start thinking outside of the so called box. What we came up with was a two part workshop that I’d like to share.

The first part was a traditional Post-it-exercise run for three different themes. First we asked the participants to list as many aspects as possible of the content we developed. They were asked to write it down on a certain color of Post-its using just one or two words. We then asked them to do the same thing on another color of Post-its but this time to list different cross sections of possible audiences; whom to reach out to. The target audiences could be sliced according to roles, geographical belonging, age or any other grouping. Finally the participants got to write down different channels for reaching out on a third color of Post-its. We got all kinds of fun suggestions; competitions, courses, lunch walks, blind dates, printed t-shirts etc.

For the second part we wanted to use an element of randomness to get the participants imagination going. Inspired by the game Clue; you know the detective game were you have a bunch of suspects, different murder weapons and a number possible crime sites. In the game, the players randomly combine a suspect with a murder weapon and a crime site by pulling one card from each pile. They then try to deduct which cards have been selected by questioning each other. Finally someone realizes that it was Coloner Mustard in the library with the candlestick.

In our workshop we now had three big piles of Post-its containing What, For Whom and Channels. We divided the participants into groups of two and asked them to randomly pick one note from each pile and try to concretize the mix of cards into an actual event. So if a group picked the cards Content A, redheads and blind dates; they then had to come up with an idea for how to sell Content A to redheaded people by arranging blind dates. The combinations that came up brought out a lot of laughter but it also generated tons of new ideas for how to market our stuff to different audiences. Surprisingly few combinations had to be completely discarded and people came up with really imaginative events from the random combinations they were dealt.

From this experience, I can really recommend trying an element of randomness when you need fresh ideas and have a problem that can be sliced in different dimensions like this.

That’s life … Not!

October 8, 2012

Do you remember the Smurfs? Little blue creatures with white hats. Three apples high. Very strong characters. The fact is that their personalities are so distinct that each one is named after it’s strongest character trait. We’ve got Clumsy Smurf, Happy Smurf, Angry Smurf, Grumpy Smurf and countless others.

They like to sing as well. At least here in Sweden they used to sing a song about everyone of us having an inner smurf. They were wrong. We don’t have ONE inner smurf; all of them live within all of us. Inside our heads, the entire smurf village is represented. Inside your head is a board of directors consisting of Papa Smurf, Angry Smurf, Poet Smurf and all the other smurfs.

The problem is that we learn at an early age that all smurfs are not born equal. Sure, we cherish a couple of them; Pretty Smurf, Smart Smurf, Kind Smurf and a couple of others while we suppress most of them. We create rules along the road for which smurf to bring out at what occasion. One of the first things we learn as newborns is to bring out Scream Smurf when we want some attention. Then, while growing up, we create new rules that benefit us better in the new situations that we have to face. But somewhere along the way we stop evaluating our rules. The rules harden and become an integrated part of us and finally we sit there with a small number of smurfs that we only let out at very given occasions.

Clumsy Smurf, Greedy Smurf, Ugly Smurf and Crying Smurf are not let out into the open if we can stop them. Sometimes we can see them in other people, representing their bad sides and sometimes we can even hear them quietly inside our own heads but they make us feel ashamed and we shut them up as quickly as possible. We suppress Egotist Smurf until he’s no longer three apples high, but only a molding apple core sitting quietly in the corner.

When we restrain these alternative sides of ourselves, we also limit our emotional degrees of freedom. We’re stuck with only one possible emotion to bring out for each situation that we have to face. Remember that there are rules for how we should behave! The situations become governing for us and we feel cornered since we don’t have any freedom of choice on how to act. That’s also when we begin to blame our emotions on the world around us.

– Oh, you make me so mad when you talk like that!

– You make me sad when you act that way.

– You! You make me feel violated.

We can’t choose what will happen to us, but we can always choose how to handle the situations and the first step towards ownership of the situation is to take responsibility for our own feelings in it. The next time you feel anger building up inside you, try not to say that “You make me sad.“. Instead, try saying “I get sad when you talk like that.” or even better; “I’m making myself sad when you talk like that.”

The rules that we have created for ourselves have at some point been useful to us but when we stop re-evaluating them, we also stop choosing rules and instead let the rules choose for us.

But what should we be doing instead? Should we throw out our old rules on how to act?

No! Don’t throw them out but start challenging them again. Evaluate them continuously and see which rules are still beneficial to you. And use them as guidelines instead of rules. There is always a choice. I can choose to get sad, I can choose to feel violated but I can also choose to ignore. I don’t have to be a victim of the circumstances because I can choose which smurf to bring out, they all belong to me.

I would like to highlight three things that we can always do to improve our possibilities for making conscious choices. These are not advanced methods and they’re not even separated from each other, they overlap quite a lot. But they do allow us to become and act as thinking creatures, capable of complex responses that match the situations we are faced with.

The first thing that often stands in our way of making a conscious choice is that we don’t take the time to consider our options.

Your kids walk up to you five minutes before dinnertime asking for ice cream.

NO!!!

You shot the answer at them in a fraction of a second as if this was a duel of life and death between you and the kid. But we don’t owe it to anyone to answer that quickly. We’re allowed to ask for time to think.

Wait a minute while I think about it.

What would happen if I let the kid have an ice cream before dinner today?

Would he get cavities? – Probably not.

Would I always have to let him have an ice cream before dinner? -No.

Or could I let him have an ice cream just to make him happy today?

If I only take a couple of seconds to consider my options, I might realize that it could be okay for me to bring out Nice-Daddy-Smurf and let him have an ice cream today.

The second thing that has a tendency to get in the way between us and our possibilities to choose which Smurf to bring out is that we don’t listen to the person we’re interacting with. We think we recognize the situation the person is talking about quite fast and then we put it into our own context and spend the rest of the time trying to come up with a good reply for when it becomes our turn to speak. If instead, we could focus on the here and now and really listen to the person and validate that we’ve heard what she has to say, then we’d realize that the situation probably isn’t what we first thought. Once we see the complexity of the situation we are able to meet it with an equally complex response that works in the right direction, instead of just conveying our simple opinion on something we thought we had heard.

The third point I would like to suggest is to reframe the situations we face. If we can change our perspective, we will also be able find new ways to act and respond. Try to find new ways to describe what you experience and use positive or neutral terms to depict situations or actions. If your instinctive reaction to someone is that the person is irritable, see what happens to your feelings if you call the behaviour passionate instead. If someone seems fearful, try and see if your feelings change if you call him careful instead.

Assume the most generous interpretation of the world around you and you’ll definitely change your view on a lot of things. You will also learn to know a much larger portion of your inner smurf village.

This post is based on a lightning talk I recently gave (and messed up somewhat) and is heavily inspired and influenced by some awesome people that I’d like to recommend for further reading on the subject.

Beverly Patwell and Edie Seashore – Triple Impact Coaching

Barry Oshry – Seeing Systems: Unlocking the mysteries of organizational life

Virginia Satir – Your Many Faces

A Sober Check-In

September 24, 2012

Today I needed to come up with a check-in for a workshop with people from different parts of the client organization. Most of the participants didn’t know each other beforehand but we were going to spend the afternoon together so some kind of introduction was necessary. A major goal of the workshop was to get people to share certain aspects of their work experiences, thus a trusting environment was an important factor. At the same time we had quite a tight schedule so I couldn’t take more than a couple of minutes for the check-in part.

Preconditions:

- People did not know each other

- Short on time

Goals:

- Get participants introduced to each other

- Get participants to talk in front of each other

- Get participants to gain some trust for each other

These preconditions and goals are common for a check-in but in most of my scenarios people either know each other better to begin with, or I have more time to spend on the check-in. What to do?

Now, I do have a relationship with Macallan and Ron Zacapa but it’s quite casual so I haven’t felt the need to attend an AA meeting yet. However, I started watching the movie You Kill Me the other day. In this film Ben Kingsley plays a recovering alcoholic so I got some insight into the format of these meetings without having to go there myself. I figured that opening up about something as personal as alcoholism in a room full of strangers requires a lot of trust and perhaps I could learn something from their format. So what would a corporate AA meeting/workshop look like?

Me: “Hi! My name is Morgan and I’ve been addicted to agile ways of working for ten years now.”

Everyone: “Hi Morgan!”

Me: “It all started when a friend gave me a white paper on XP and before I knew it I was using Scrum and TDD on a daily basis.”

What do we have here?

First; a presentation. I tell everyone my name and something about my qualification to be in this room. Now I’m not a complete stranger anymore.

Second; one of the oldest tricks in the book when it comes to remember people’s names is to repeat the name immediately after you’ve been introduced. So we also have increased everyone’s chance of remembering the names of the other participants by having them say “Hi Morgan!”.

Third; for me the feeling is that everyone welcomes me by saying “Hi Morgan!”. They have recognized me and my presence and they know my name.

Finally; I get to share something about where I come from so we can find some common ground during the day.

This AA-style presentation took about 30 seconds per person and was not more advanced than a simple round the table presentation where everyone states their name and their role but my experience was that the details made quite a lot of difference. The participants felt a little bit silly about the format so some chuckles eased the mood without taking away the fact that people felt recognized and welcome. Everyone shared something and everyone spoke in front of each other. I will definitely use this format again.

Sucker Punch To My Agile Ego – Part 2

June 15, 2012

The other day, as I arrived a bit later than usual for work at one of my clients, I was immediately called into a meeting without any prior notice. When the meeting began I was told that the purpose of it was to discuss strategies on how to support the entire organization in projects working with external service providers. The people in the meeting were all representatives from different support functions within the organization. Everyone was discussing how to divide the responsibilities of supporting the rest of the organization from different perspectives. I was nodding in agreement whenever someone said something that sounded good to me, and every now and then I asked for a clarification when there was something I didn’t understand.

Now, this was outside of my expertise and I don’t really know anything about buying external services so I started going through possible relevant knowledge in my head while at the same time listening to everyone else. The only thing that came to my mind was what I had read in “Freedom from Command & Control” by John Seddon. A main theme of the book was how a service organization should be designed from the outside and in; to always begin with the customer perspective. The book is written from the perspective of the service organization but I figured that this ought to be good to consider as a buyer of services as well. A good criterion in the supplier selection process should be that they work according to the principles listed by Seddon. So while we were doing some friendly territorial peeing between the departments on who should provide what service to the rest of the organization, I was trying to figure out how to explain Seddon’s thoughts to the others and the rest of the organization.

That’s when my invisible friend kicked me in the groin and yelled “Stuuuuuuuupid!!!” in my ear. “You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your brother’s eye.” My eyes were swelling up from the pain of this sucker punch as my inner voice continued; “Your mind is filled with how to teach others how to design a service organization from the outside in while you all are designing your own service organization from the inside out. You are sitting here making up your own ideas on what support to provide the rest of the organization without any representation from your customers.”

After the initial chock had worn off, I wiped a tear out of my eye and swallowed a couple of times. I then raised my hand to get the attention of the room. When I had everyone’s attention, I spoke up; “What if we turn the question around? What if we ask the organization what support they need and then organize ourselves in the best way to provide this service?”

There was a long silence and I wasn’t sure if they all thought I was out of my mind or not, but then everyone started nodding. “Yes, that might be a good idea. Perhaps we should look at the need before we try to provide a solution.”

I don’t know if anyone noticed my pain and I never mentioned the sucker punch but my conscience about not pretending that I had walked down that horrible dark alley of ignoring my customers has been bothering me since so I figured that sharing this story might ease my mind a bit. We’ll see if it helps.

Who Speaks for Wolf on Your Team?

May 24, 2012

This post is based on a lightning talk I gave at a client and is heavily inspired by the excellent book “A Practical Guide to Distributed Scrum” as well as my own experiences from working with distributed teams.

_____

Paula Underwood, a Native American (Oneida – Iroquois) historian, wrote down the 10.000 year old oral history of her tribe. Among the stories that she shared there is one particular learning story called “Who speaks for Wolf”.

Paula Underwood

The story describes a time when the tribe had outgrown its current habitat and was looking for a new place to live. They sent out many young men in different directions looking for the perfect spot for them to move on to. When the men came back the tribe evaluated the places found on different criteria such as access to water, suitability for growing their seeds, animals to hunt and so on. Finally they decided on an area that had the potential to fulfill their needs. The problem was that a large population of wolves also inhabited this very spot. One of the men in the tribe, called Wolf’s Brother, who was very close to our feline friends, spoke up against this decision. He told his peers that there wasn’t room enough for both man and wolf in this place, but his words were ignored.

Soon enough though the rest of the tribe realized the correctness in Wolf’s Brother’s prophecy, that too many wolves where competing with them for the same food and that they wouldn’t be able to chase the pack away. Instead they decided to hunt down the wolves and exterminate them from the area. Luckily, they came to their senses at the last minute and realized that this would change the people into something they didn’t want to become; “a people who took life rather than move a little”. With this insight they changed their decision and moved to another area and left the wolves alone.

In order to not let this story repeat itself, to make sure that someone always took nature into consideration when they made any decisions, someone would always raise the question:

“Tell me my brothers,

Tell me my sisters,

Who speaks for Wolf?”

When we are working in distributed teams, we are often confined to teleconferencing. And when we’re facilitating a teleconference it’s easy to forget that there are people on the other side of that line who don’t see what we see. It’s easy to fall into the trap and act as though everyone were in the same situation as we are. In order to not forget about our friends on the other side, it can be a good custom to make sure that there’s always someone who speaks for Wolf. Someone who looks after the interests of those on the other side of the line.

What you can do is to nominate someone in your team to be the patron of the people on the other side. Have someone, preferably someone who has also been one of the people on the other side, to watch for, and to call out non-remote friendly behaviors so they come to everyone’s attention.

So what are non-remote friendly behaviors?

One thing to look for is visual cues. Those usually don’t travel well across phone lines. Ask for visual cues that you don’t see or translate them when you do see them.

Say for example that you mention a new requirement that your team has been asked to bring into your next sprint. No one in the room opens their mouth but Paul and Jill are making gagging faces showing that they consider this to be a horrible idea at the moment. Let the people on the other side know what is happening.

“Okay, I don’t know what you’re thinking about this new requirement in Hyderabad but Paul and Jill are making really funny faces about it right now.

Or perhaps someone makes a reference to some tension that happened in your last meeting and you’re not sure if this is water under the bridge or if the tension is still there. Ask!

“Yeah, that was quite a disagreement we had last week. Jane, are you smiling now or does this still put a frown on your face?”

Every now and then someone forgets about the non-present part of the meeting and starts to point at the screen while commenting, or even worse; starts to draw on the whiteboard. Let people know what is happening.

“Ok, now Peter is pointing at the column with last years figures, just so everyone knows what he’s referring to.”

Or:

“I’m sorry guys that you can’t see this but Jill just drew a pie chart here showing that 45% of the functionality must be done this quarter. Perhaps Jill can take a photo of it and email it to you after the meeting.”

Anyone should be able to call these things out but if you have a patron of the people on the other side, responsible for keeping an eye on these things, it will make everyone more aware of them.

Another problem, especially for new teams, is that it can be hard to tell whose voice it is you’re hearing. So always try to identify the speaker. Before you begin to say something it’s good to identify yourself.

“Okay, Jane here. I think we need to reconsider those numbers you just presented.”

But if Jane forgets to present herself, the patron can move in with a short:

“Thank you Jane for that comment.”

just to let everyone know who spoke out.

These are just a few examples of misbehavior that cripple the communication within a team. There are many others and learning to see them takes time. But if your patron of the people on the other side, calls out these misbehavior people will begin to see the patterns and start correcting themselves.

So tell me my brothers,

Tell me my sisters,

Who speaks for Wolf on your team?

For whom was the sticker made?

November 7, 2011

A couple of days ago, as I was grabbing my bag out of the overhead compartment on the quite small plane I had taken between Newark and Raleigh/Durham, I noticed a sticker in the back of the compartment. Most planes I have flown with were bigger and I’m just not tall enough to see that far in so I don’t know if the sticker is always there but in this plane it was at least. The picture I managed to take is quite blurry but what it says is: “MAX. CAPACITY 60 LBS/27 KG”.

Great, they don’t want the compartment to fall down on the head of some poor schmuck sitting under it.

I don’t know what’s wrong with me but I immediately wondered why they put that sticker there. What is the difference between having that sticker and not having that sticker?

Let’s pretend you’re a passenger and you are the first one to put something in the overhead compartment and you actually manage to see the sticker. What goes through your mind? Probably nothing much. Most of us have a bag that weighs less than 10kg but that doesn’t really matter because we don’t know what it weighs anyway. So you put your bag up there. Next person comes along. If she can still se the sticker after you’ve put your bag in there, what will she think? Probably that her bag is lighter than the limit. She has no idea how much your bag weighs and she most certainly won’t take it out and try to estimate the combined weight so she puts her bag in there as well. If there’s still any room up there, no one will see the sticker because of the bags and jackets already there and they’ll keep loading their bags.

Let’s pretend that the airplane manufacturer put the sticker there because they were concerned for the safety of the passengers. Jerry Weinberg uses the expression that you should eat your own dog food, meaning that you should try your own products for yourself before exposing them to your customers. If the manufacturer had actually tried to board the plane and recorded how the sticker changed their behavior they would probably have come up with zero.

But what if the sticker wasn’t even the manufacturer’s idea. What if it is some government agency that is looking out for us, the passengers? Did they make a rule that says that the manufacturer must make sure that no one gets an overhead compartment in their head? Did they express it in such a way that no one will get an overhead compartment in their head? They might have said that the manufacturer is liable for informing the passengers about the maximum load. But they certainly did not say that the manufacturer is liable for making sure no one gets hurt. Because if they did, that sticker would not have been there.

Now I don’t know who decided that there should be a sticker there and for whom it was made and

Therefore, I send to know

for whom the sticker was made,

it wasn’t for me.

Enough of paraphrasing John Donne and back to the game. If the purpose of the sticker truly is to save people from getting an overhead compartment in the head and not just a way of keeping the manufacturer out of court when someone has been hurt, then I consider it to be an example of poor problem solving and I’m more interested in good problem solving so I’m asking you, dear reader:

What would you have done to prevent people from overloading the overhead compartment?

Explicit Expectations Exercise

October 28, 2011

Assumptions is the mother of all … flurps.

I would say that the majority of our failures in cooperation and collaboration arae due to assumptions. We also fail largely due to poor or lacking communication but this is based on an assumption that we don’t need to communicate in order to succeed.

I’ve seen so many problems arising from people making assumptions about other people. We prefix a lot of our statements with “I think that … ” or “I believe that …” and yet we continue acting based on the statement that follows. What is up with that? Shouldn’t the words “I believe …” raise a warning flag so red that it would have brought a tear to Karl Marx’s eyes?

My suggestion is that whenever you hear yourself or someone else utter words to that meaning, you should challenge yourself or the other person to validate the assumption.

I use those words all the time and I want someone to challenge me since that will provide me with great opportunities for learning.

When it comes to teamwork, I find that a lot of assumptions take the form of implicit expectations. We expect people around us to behave in certain ways and we assume that they know this and that they will act accordingly. This is a breeding ground for bad feelings and even less communication because we often attribute peoples failure to live up to our expectations to spite on their part. In an attempt to lessen the frequency and impact of these hidden assumptions I’m designing an exercise to help make our expectations more explicit. I’ve only run it a couple of times so far and have updated the format every time and I welcome any and all suggestions for improvement that you might have but I will describe the exercise as I plan to run it the next time.

Part 1:

I begin the exercise by creating columns on a whiteboard, headed by the different roles in the project; project manager, product owner, ScrumMaster, developer, tester etc. I’m aware that Scrum only prescribes three roles but the goal of this exercise is to make things explicit, not wishful thinking. I also ask a representative for each role to act as secretary for the second part of the exercise. I then hand out pens and Post-It notes to everyone present (all roles from the columns need to be present for the exercise to be meaningful). Then everyone gets to write down their expectations on the different roles on the Post-It’s, and post them in the column for the role they have expectations on, as they write them. The expectations are written on a format similar to user stories;

“As a ‘role‘ I expect ‘another role‘ to ‘fulfill some expectation‘ so that ‘some benefit will occur‘.”

I might for example post the following expectaion in the Product Owner-column:

“As a ScrumMaster I expect the Product Owner to be available for the team members at all times during the sprint to answer their questions about requirements so that they don’t have to guess what the customer needs.”

I give this part about 10-15 minutes or stop it when no more notes are being produced. People usually need some time to think during this exercise and they tend to write during the time available.

Part 2:

Then I go through role by role and note by note, asking for clarifications if needed, and also asking the representative(s) for the role if they intend to live up to the expectation on the note. I will ask the secretary to take additional notes from the discussion. Usually people want to live up to the expectations but not without clarifying what is meant;

“What do you mean by ‘at all times’?” and “What do you mean by ‘available’?“.

Sometimes the expectations are off, it can be a project manager expecting team members from a Scrum team to report progress to him or a developer expecting a product owner to add every technical story they can come up with to the backlog. The discussion around these expectations is really important because it will clarify and set boundaries. It will validate or invalidate assumptions. I have found that for a group of 15-20 persons this part of the exercise will take about one hour if it is heavily moderated. Make sure that you have enough time for this discussion because this is an investment that will pay for itself.

Part 3:

After the exercise I ask the secretaries to take home and rewrite the accepted expectations as a contract, with any clarifying notes from the discussion added. The expectations should be turned around and rephrased as commitments.

For example:

“As a Product Owner I commit to be available, at least by mail and phone, five days a week for the team members, to answer their questions about requirements so they don’t have to guess what the customer needs.”.

The contracts are then to be signed or at least acknowledged by everyone representing the role.

The main goal of the exercise is not to produce contracts but to bring out as many assumptions and expectations as possible into the light. The contracts are just reminders about the exercise and a way of repeating what was agreed upon one more time after everyone has had a chance to digest the exercise.

This exercise can be done as an activity at the beginning of a project as well as later on if you experience communication issues in your project and suspect that they might stem from hidden assumptions. If you run this exercise, please share your learnings here so I can continue to improve it.

You can’t stop people or yourself entirely from making assumptions but you can tell other’s about yours and you can as them about theirs.

You are always in the blind spot – Let the coach expand your field of vision

September 15, 2011

As a leader – or team member as well for that matter, you are faced with a big problem every time you try to implement some sort of a change in your organization.

No, that’s not true. You face a lot of big problems, but one of the bigger ones is … you.

You are trying to interfere with a system without being able to see the entire system. You need to get a helicopter view of the landscape while at the same time being grounded as an important part of the very same landscape.

Most of us don’t understand how much we affect a system that we are a part of, and more importantly; we don’t understand in what ways we affect that system.

Our presence in a meeting can set the entire tone of it without us doing anything in particular. Likewise, we can also affect the outcome of a meeting just by being absent from it.

How do we interact with our systems? What messages do we send to them? Do you have a total coherence between your thoughts, your words and your actions? If not, what parts of your intentions and your communication are getting across? Vice versa; what parts of your coworkers’ true intentions get across to you.

How can we possibly know how a system will react to a particular change if we can’t see the entire system?

Being a lean/agile coach, I’d like to suggest that you get yourself a new set of eyes and ears. As a leader or team member, it’s your duty to be a part of the landscape. You must be the intricate part of the machinery that you are. I, as a coach on the other hand can reserve the right to stay outside your particular system. I can put my stethoscope to the heart of your organization and listen without the distorting filters of preconceptions and interfering echoes of my own actions.

(… at least for a while. Sooner or later we all get biased.)

There are also tools like the left hand column exercise and Virginia Satir’s interaction model that can help us learn to see how our own behaviors affect those around us. If we accept the help and take the time to study ourselves, we can begin to move out of our own blind spots and get our helicopters in the air.